Post Malone: Nice work if you can get it

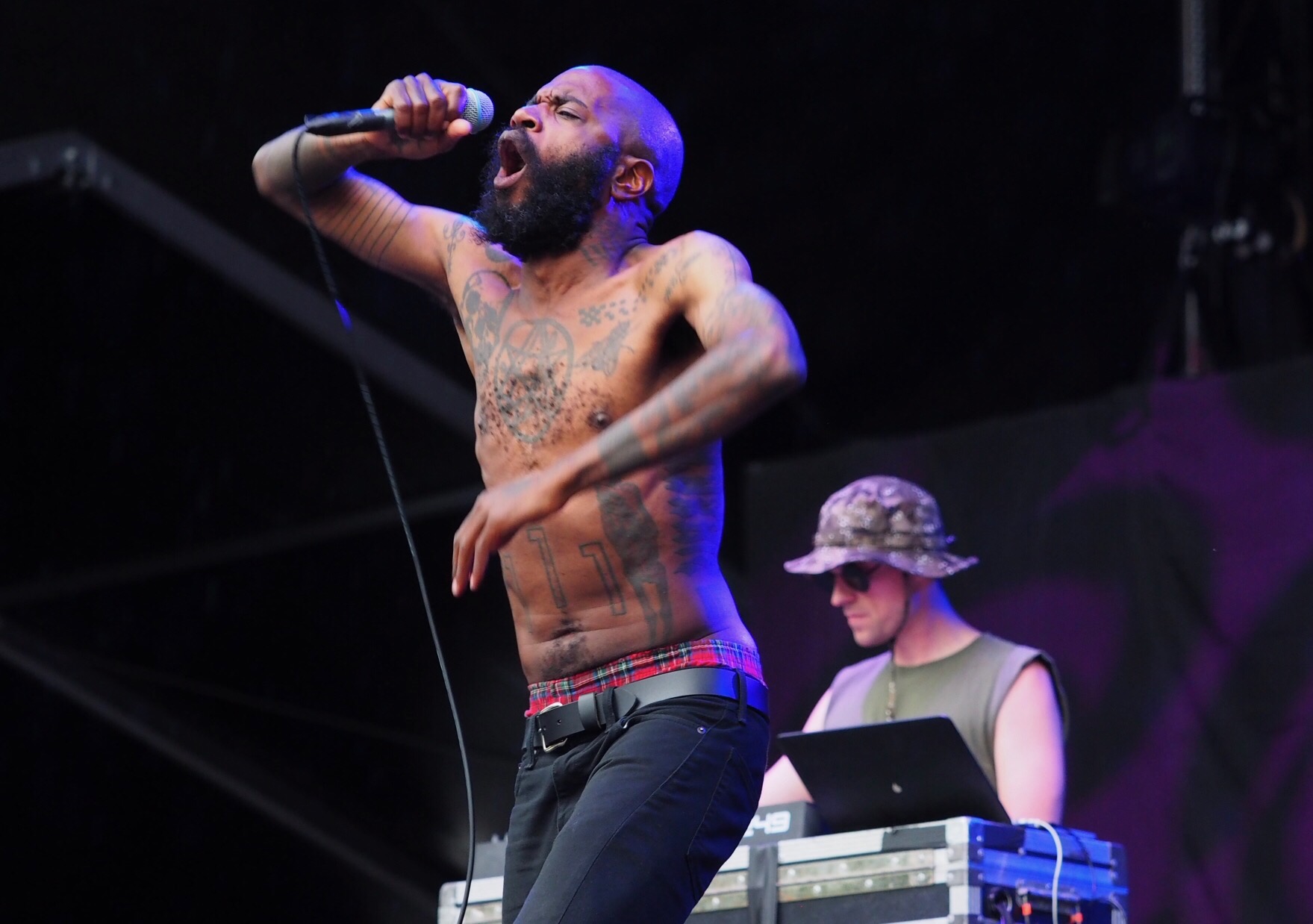

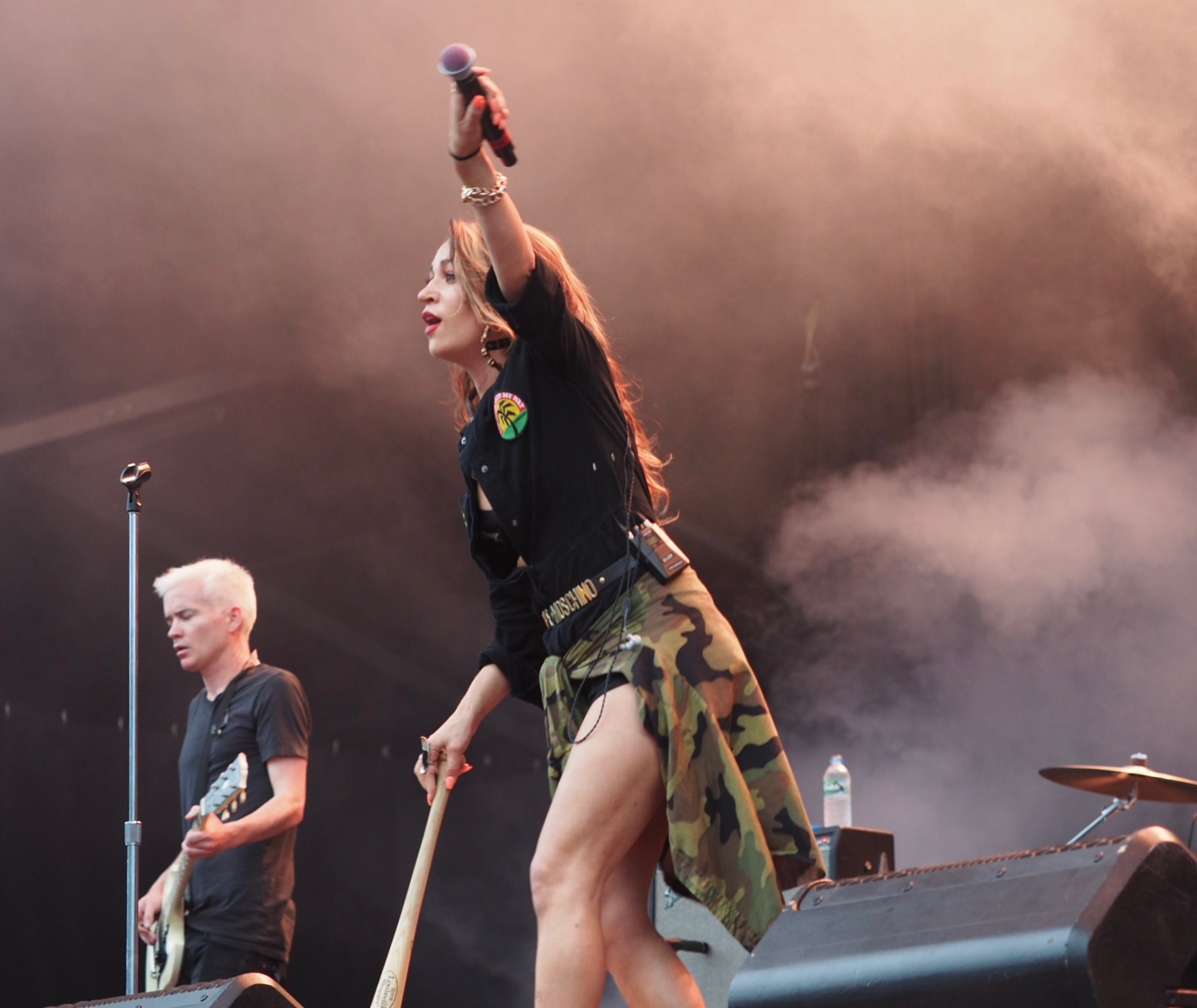

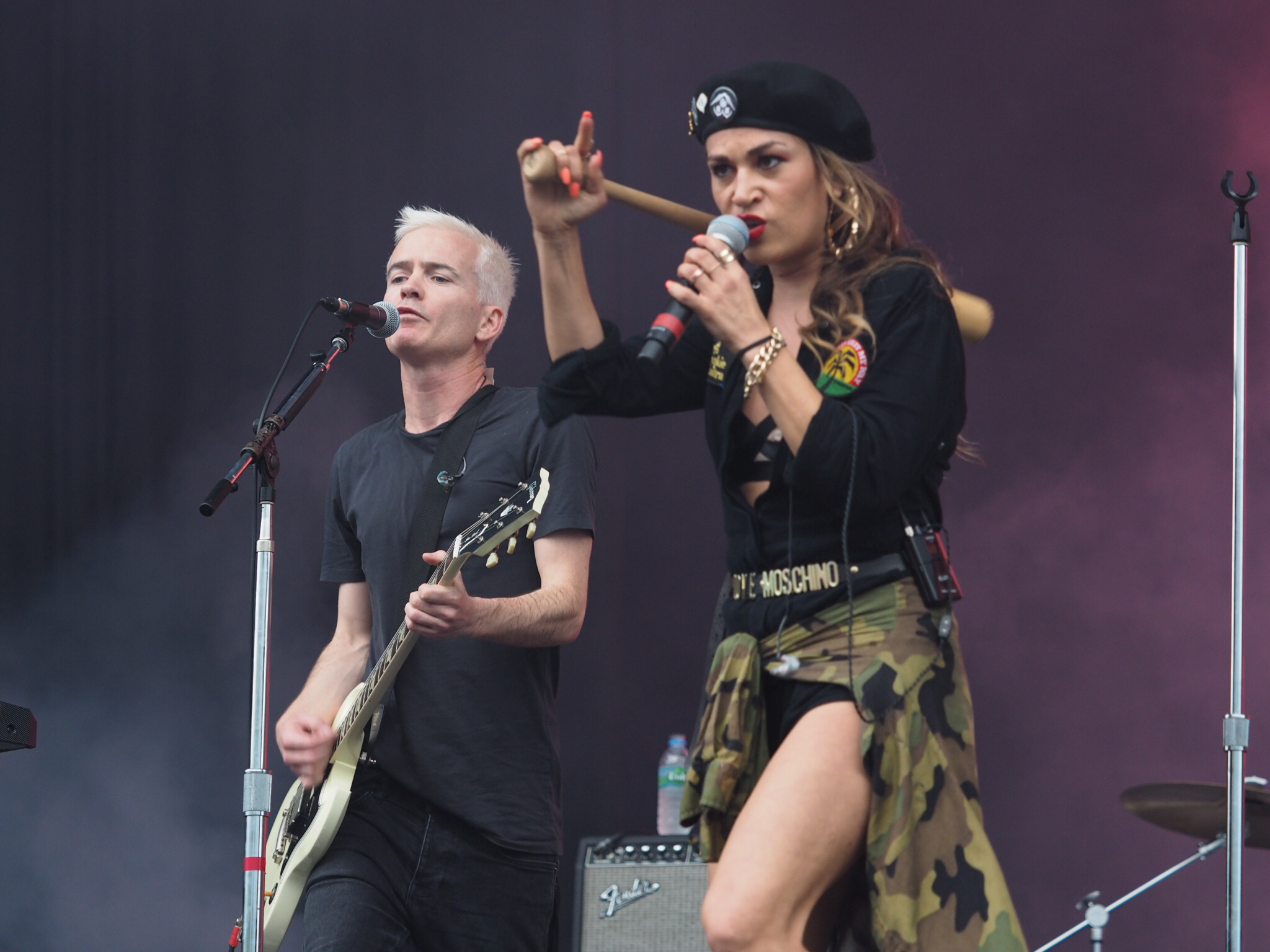

The rapper Post Malone made his Japan debut at the White Stage headliner on Friday. Given that his show started 15 minutes after N.E.R.D’s ended, security expected huge numbers of people to make the trek from the Green Stage, but it didn’t really happen. Though it might be assumed the same kind of people like both N.E.R.D and Post Malone, one of the most popular hip-hop artists in the US right now, that isn’t necessarily the case, and it’s not so much that Post Malone is white. It’s mainly that his fans are.

And whether it was sign of confidence or hubris, he was alone: no musicians, not even a DJ. Just recordings, including his own raps that he doubled upon. That said, he gave a passionate performance and seemed truly humbled by the reception. But one couldn’t shake the feeling that it was all set up to make him happy rather than the fans. He was drinking beer throughout the show (once out of a sneaker) and stated unequivocally that he intended to “get fucked up.” I mean, isn’t that what the festival goers are supposed to do?